Reyna Martinez DeJesus stood before a line of smoking grills at the back of “Ricos Tostaditos,” a Mexican food stand at the Northway Mall Farmers’ Market. Tall pots, tightly covered and steaming, crowded two of the grills. On another, flank steaks cooked over flame, sending their tantalizing aromas out into the market.

Reyna Martinez DeJesus stood before a line of smoking grills at the back of “Ricos Tostaditos,” a Mexican food stand at the Northway Mall Farmers’ Market. Tall pots, tightly covered and steaming, crowded two of the grills. On another, flank steaks cooked over flame, sending their tantalizing aromas out into the market.

The irresistible smell of grilled meat drew me over. I ate some in a tostada, dressed with fresh homemade salsa and hot sauce. I wanted more of Reyna’s food. I ordered pozole, traditional Mexican soup made with hominy corn and finished with red chile sauce, intending to take it home for lunch. I tried taking just one bite, to see how the chile sauce tasted. It was amazingly good. Before I knew it, I’d powered down every bit of the pozole.

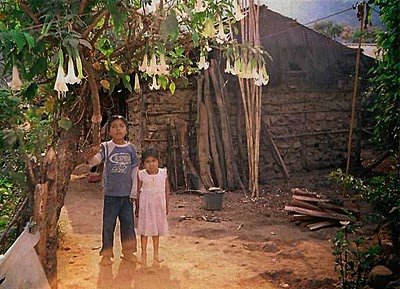

During repeat visits to Ricos Tostaditos, I learned Reyna, 35, her husband Lorenzo DeJesus Flore, 40, and their six children are Triqui, an indigenous people from the mountains of Oaxaca, a southern Mexican state. Triqui, not Spanish, is their primary language.

So how did a family of Triqui end up in Anchorage, Alaska? It started with Lorenzo’s decision to leave his violent region for the United States.

“I was afraid. Every day, afraid,” said Lorenzo, describing his youth in San Juan Copala, a Triqui region in Oaxaca. “No schools, we can’t walk outside, can’t do nothing, just stay inside, because always they come in from outside village and shoot us. No school, no teacher, no clinic, no hospital, only fighting, fighting, fighting. Various factions want you to join them, if you don’t they kill you. Have to ask permission of factions to travel, if you don’t they kill you. If I stay in San Juan Copala, they kill me. I went to US to stay alive.”

Lorenzo’s description of San Juan Copala’s violence has been documented by Amnesty International and the Center for International Policy’s Americas Program; the evidence shows murders are commonplace. No one is immune from harm. Small children and the elderly have been randomly killed, as have community leaders and human rights observers.

The cause of the violence is complex, and seems inextricably tied to the Triqui resisting control and domination from outside their culture. That resistance has been used and exploited by an alphabet soup of organizations, all claiming to speak for the Triqui people, and ready to shoot, kidnap, and torture anyone, of any age or nationality, who gets in their way.

When I asked Lorenzo the reason for all the violence, he said many factions and people wanted power in San Juan Copala, leaving the Triqui people caught in the middle. When I asked about the factions’ goals, asking which was right or wrong, Lorenzo said, “There isn’t any right, all is wrong.” Violence has taken on a life of its own in San Juan Copala, he said.

“Too many innocent people are suffering. The people suffering don’t care about power.” Lorenzo said, “Does power matter to old people? To children? If mother or father is killed, what does power for faction mean to family? Nothing. Means nothing.”

Lorenzo and Reyna learned this lesson first hand. When Reyna was 4, her 22-year-old father was murdered. Why? Because he spoke Spanish and could read, Reyna’s father was seen as a potential threat to those in power. Lorenzo’s father was shot in the back outside his house and permanently disabled; as she dragged her injured father into the house, his sister was also shot. Why? ”No reason.” Lorenzo said gunmen “hide in hills outside villages and shoot so you never see them and never know when and where the shots are going to come.”

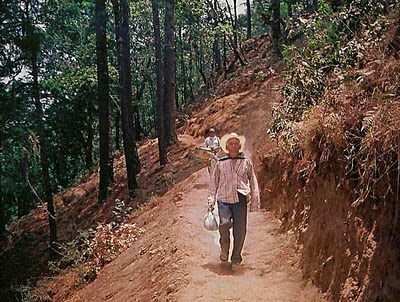

In the San Juan Copala region, “roads are closed. If people use roads, they get shot. They have to walk everywhere.” When asked why people have to walk, Lorenzo said, “To stay under cover, not out in open. Mountain paths are safer, but hard because steep. Very steep. It’s a hard life. For old people, if they need doctor, they walk four hours from one village to far away village that has safe road to drive to doctor. If they can’t walk, then no doctor, no medical care.”

In the San Juan Copala region, “roads are closed. If people use roads, they get shot. They have to walk everywhere.” When asked why people have to walk, Lorenzo said, “To stay under cover, not out in open. Mountain paths are safer, but hard because steep. Very steep. It’s a hard life. For old people, if they need doctor, they walk four hours from one village to far away village that has safe road to drive to doctor. If they can’t walk, then no doctor, no medical care.”

“It’s luck I’m alive,” said Lorenzo, deeply serious. He described a planned market trip with a group of friends. Chance made him miss the trip; his friends were all shot and killed on the road to the market. Why were they killed? “No reason,” said Lorenzo. “Bad luck.”

Lorenzo made his escape from San Juan Copala as a teenager, coming to the United States and earning a green card. He worked in California’s farm fields and New York restaurants. Lorenzo met and married Reyna on a trip home in 1991. Soon after the marriage, Lorenzo returned to work in the US, sending money to Reyna and visiting whenever he could. In the village, Reyna lived with her mother, raising corn, squash, and their growing family. Lorenzo came to Alaska in 2001 chasing rumors of high-paying jobs in Dutch Harbor, but quickly found work in Anchorage and never left.

After 25 years in the United States, Lorenzo has worked hard to achieve the American dream. He became an American citizen 4 years ago. Once he became a citizen, Lorenzo was able to bring his wife and children to Anchorage, taking them far from the violence of San Juan Copala.

After 25 years in the United States, Lorenzo has worked hard to achieve the American dream. He became an American citizen 4 years ago. Once he became a citizen, Lorenzo was able to bring his wife and children to Anchorage, taking them far from the violence of San Juan Copala.

With these achievements, I asked Lorenzo what he wants from life, “I want my kids in school and learning. I want them to be nice people. I want them to help others. And I want to make a difference for the Triqui people, to get them help, to stop all the shooting, all the dying.”

I asked Lorenzo what would help the Triqui people. He said, “I wish government would do something for the poor Triqui people. They don’t speak Spanish. They don’t know nothing. They don’t know why these people are fighting. They know only babies dying. Old people dying. Women dying. For no reason. Maybe we could teach Triqui Spanish? Maybe that would help, I don’t know.”

“But I do know, if this happen in big city, all these people dying, being shot, it would be on TV all day, all night. Every day, every week, it would be on TV. Even if it happen to animals in big city, it would be on TV. Someone would do something. Government would do something to stop the killing. Not just let keep going on and on. But for Triqui dying in far away villages? No, nothing happens. No one knows. No one cares. Like Triqui are invisible. They just keep dying and no one sees, it’s like didn’t happen.”

Lorenzo is not alone in seeking government assistance for isolated Triqui villagers. A group of Triqui women and children from San Juan Copala are now living in a tent city in the center of Mexico City, calling on the government to bring back the rule of law to San Juan Copala and protect them from violence. In August, other Triqui women sought help from the UN Commission on Human Rights (this effort fell apart after three organizers were murdered and two others seriously injured).

Lorenzo is not alone in seeking government assistance for isolated Triqui villagers. A group of Triqui women and children from San Juan Copala are now living in a tent city in the center of Mexico City, calling on the government to bring back the rule of law to San Juan Copala and protect them from violence. In August, other Triqui women sought help from the UN Commission on Human Rights (this effort fell apart after three organizers were murdered and two others seriously injured).

Lorenzo and Reyna told me their story when I was at their house learning how to make Reyna’s Chicken Mole. I wanted a cooking lesson. Lorenzo wanted somebody, anybody, to know what is happening to his friends and family in San Juan Copala. In this article, I’ve scratched the surface of a complicated, fascinating story. If you know of a good writer in search of a book topic, someone who’d gladly travel to dangerous mountain regions of Oaxaca, tell him or her about the Triqui. They need a voice.

As for Reyna’s Chicken Mole, like every bite of food that Reyna makes, it’s delicious.